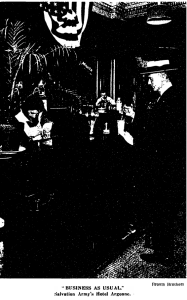

The Hotel Argonne, W47th Street, NYC. A Salvation Army dry saloon opened weeks before Prohibition came into effect on July 1st, 1919.

In its humble beginnings, The Salvation Army was regarded by bar owners (referred to as publicans) as persona non grata. The Army’s focus on holiness and sober living was seen as a threat by drinking establishments in Great Britain, to the point where bar owners would encourage their patrons to attack members of The Salvation Army wherever they were found. Fortunately, this changed when publicans saw the good that The Salvation Army was achieving in the communities of Britain, to the point where salvationists were allowed to witness in the pubs by selling War Crys, and by providing spiritual counsel to bar patrons. Countless testimonies affirm the value of the Salvation Army’s pub ministries.

On July 1st, 1919, with the ratification of the 18th Amendment, the sale of alcohol was officially outlawed in the United States. The era known as Prohibition, came into effect and with it, New York City’s 10,000 drinking establishments could no longer legally sell alcohol. Many went out of business.

Sensing an opportunity to do some good, The Salvation Army rose to face this new era with determination and innovation. What would drinking dens look like, sans the drink? Was it possible to redeem the idea of a bar as a place of true community, a place like in the sitcom Cheers (1982-1993), “where ev’rybody knows your name, and they’re always glad you came?” The Salvation Army thought so. An article from the New York Times dated just weeks before prohibition came into effect, details The Army’s fascinating new endeavor:

The Salvation Army’s Hotel Argonne on West 47th Street (now the sight of Times Square Corps) was among The Army’s first notable forays into the dry saloon business. The soft drink, Canada Dry was one such popular item served during this time. When Prohibition ended in 1933, The Army’s experiment with dry saloons came to end, though the general idea lives on in Salvation Army-run coffee shops, pub ministries, and wherever Salvationists gather to form an authentic, Christ-centered community, in the midst of a hurting world.

Salvation Factory An Imaginarium Focusing on Research, Development and Design of Resources.

Salvation Factory An Imaginarium Focusing on Research, Development and Design of Resources.